South Africa’s last remaining white shark stronghold under threat

Rio Button

November 25, 2020 · 8 min read

The Oceans Research Institute battles the impact of demersal longline fishing to safeguard great whites prey base

How demand for ‘shark with fries’ down under, is contributing to the disappearance of great white sharks in South Africa

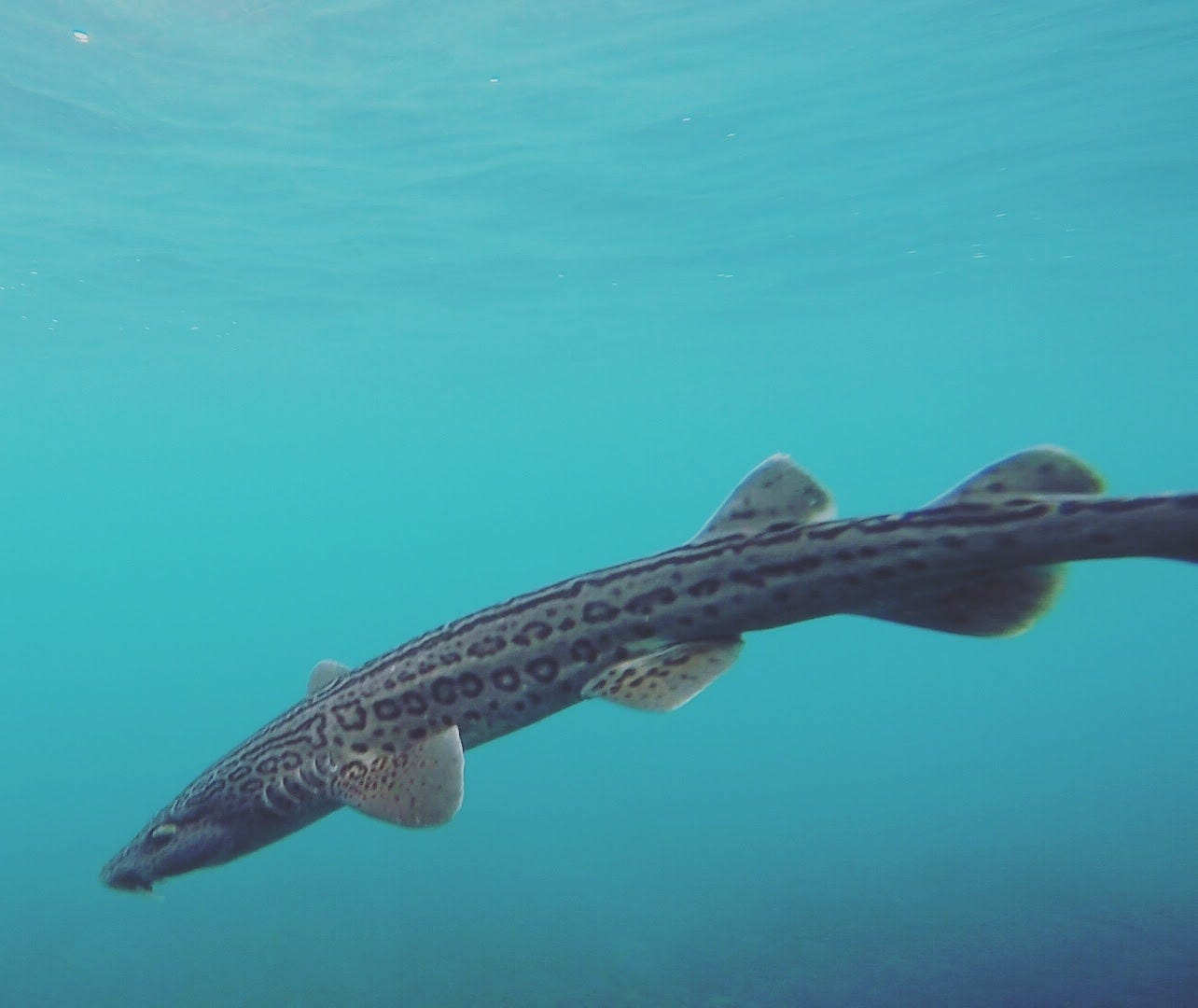

South African smooth-hound and soupfin sharks are being deep-fried and sold as flake and fries down under. Australia has a well-managed smooth-hound shark fishery, but because of demand, greater than sustainable supply of these sharks in Australia, they are importing sharks from elsewhere and increasingly so from South Africa. The South African fishery of sharks that are sold as flake in Australia are less than well managed. In fact, last year’s scientific assessment by South Africa’s Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries, discovered South African smooth-hound and soupfin shark populations were fished unsustainably, with soupfin having a 60% chance of being classified as Critically Endangered when assessed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List, which is the global authority on the conservation status of animals and plants. The overexploitation of these medium-sized sharks is removing key prey species for South Africa’s most iconic shark species.

Why did South Africa’s Great Whites disappear, and are they gone for good?

Great white sightings have plummeted at two of South Africa’s three great white hotspots, namely Gansbaai and False Bay. False Bay went from on average 205 great white sharks sightings a year between 2010 and 2016, to 50 sightings in 2018, and no sightings in 2019. This according to Shark Spotters, a shark conservation and research group that has spotters on the mountains around False Bay looking for sharks daily. Independently of Shark Spotters, just two confirmed sightings of a great white have been made in 2020. In 2017, cage diving operations in both False Bay and Gansbaai reported sharp declines in Great White shark sightings and no sightings since 2019.

What could scare a great white shark?

Bigger, more cunning apex predators, frequenting great white hotspots more often to feed on great whites, were initially blamed for scaring off the iconic sharks. These predators were killer whales, which are in fact the biggest species of dolphin and not whales at all. Killer whales are social creatures that live and hunt in packs. Different types of killer whales specialise in feeding on different types of food. There is a theory that a type of killer whales specialising in feeding on sharks started coming inshore and visiting South Africa’s great white hotspots in 2015. After these killer whales moved through great white hotspot areas, great white sharks vanished from those areas for a few weeks or even months, however, they would always return, that is until 2019 when they stopped coming back into the waters of False Bay and Gansbaai. Shark scientists argue whether the few attacks on white sharks by killer whales in Gansbaai could really have driven great whites away. Dr Enrico Gennari from Oceans Research Institute raises the point that great white shark numbers were on the gradual decline in False Bay before the first sightings of the killer whales began. So maybe killer whales are not entirely to blame for the disappearance of great whites?

What if it’s not just the killer whales?

Don’t be duped by the convenient narrative of killer whales driving great white sharks away from False Bay. Gennari believes that the disappearance of great white sharks in False Bay likely has more to do with the obliteration of populations of smaller shark species, rather than the killer whale narrative. Gennari explains that “there’s plenty of evidence that the great white sharks rely on small sharks.” As smaller sharks have been shown to be a major component of great white sharks diet, in South Africa and Australia. However, in Gansbaai Gennari believes it is both the lack of smaller sharks available for great whites to eat and the killer whales keeping them away.

Gennari tells me the decline in white sharks in False Bay started in 2013 while the two “shark-eating” orcas appeared only in 2015. In 2011, there was a rise in demersal longline fishing for smaller sharks, likely to satiate Australian’s rising demand for flake. Demersal shark longline fishing vessels deploy long fishing lines with hundreds of baited hooks attached and leave these to “soak” on the seafloor. These shark specialist vessels have concentrated fishing effort acting like a vacuum cleaner sucking up all sharks in an area before moving to the next area. Gennari stresses that “we need to manage these resources [smaller sharks, which great whites feed on] to ensure the conservation of great white sharks in South Africa.” Another factor contributing to the disappearance of great whites could be ripple effects of climate change causing changes to species distributions such as small pelagic fish. Exact mechanisms for the disappearance of great whites are speculative.

Safeguarding the last remaining great white shark stronghold

Great whites have not vanished from Mossel Bay, but why? The Oceans Research Institute has reported that killer whales come into the bay less frequently than they do in False Bay and Gansbaai, and that there is still an abundance of smaller sharks for great whites to prey on in Mossel Bay. Though Gennari tells me that “the demersal shark longliners [fishing vessels targeting sharks] are moving in [to Mossel Bay] more and more often.” The Oceans Research Institute, headed up by Gennari, meticulously gathers data on marine animals in Mossel Bay, including sharks both large and small.

This data provides invaluable evidence that where demersal sharks are still present great white sharks appear regularly. This data and the ecological understanding it provides will be essential in advising policy so the prey base of one of South Africa’s most iconic marine animals in its last remaining stronghold can be safeguarded.

Ocean Research Institute partners with Wildcards!

New Wildcards will be launched to raise funds for the Oceans Research Institute. Each card has a captivating, fact-filled story about an individual animal, which the Oceans Research Institute researches aims to protect and help better manage, including sharks great and small. You’ll be able to publicly buy one of these Wildcards online, which will make you the guardian of that Wildcard animal. When you buy a Wildcard, you must set the price you are willing to sell it for. Every month, as the guardian of a Wildcard, you will give a specified portion of the selling price you set, to that animal’s representative conservation agency, in this case, the Ocean Research Institute. At any point, someone can buy the Wildcard from you, at the selling price you specified. When someone buys the Wildcard from you, they must set a selling price. The new guardian of the Wildcard is then responsible for giving the new monthly subscription. And so the cycle continues, to generate funds.

Wildcards is ecstatic about connecting funders with conservation agencies having a real world impact on the protection of wild animals at risk.

Also read:

Wildcards: an unprecedented means of funding conservation

Follow Wildcards on twitter: @wildcards_world

Follow Wildcards on Facebook: @wildcards.conservation

Join us on Telegram: Telegram

Rio Button

Dr Seahorse’s journey

From unravelling seahorses’ secret sounds to safeguarding the habitat of these little super dads. St...

Rio Button

June 29, 2022 · 5 min read

What wild animal leaves teddy bear footprints behind?

Photo by Helena Atkinson. Photo by Helena Atkinson. Here are some clues… Using their sticky tongues,...

Rio Button

February 07, 2022 · 9 min read

Tech innovation: Solving wildlife conservation's greatest challenge

Tech start-up Wildcards has raised over 130,000 USD for conservation organisations around the world ...

Rio Button

August 24, 2021 · 7 min read

Curious creatures under persecution

From having a deep fear of sharks to defending them. Reluctant, Grant Smith tumbled backwards off t...

Rio Button

July 26, 2021 · 8 min read

NFT Postcards for a purpose

NFT Postcards for a purpose A limited edition set of NFTs has been created in partnership with the T...

Jason Smythe

April 01, 2021 · 2 min read

Do you Care for Wild?

As rhino poaching soars, what happens to the orphaned rhino calves left behind? An orphaned baby bla...

Rio Button

February 24, 2021 · 7 min read

Where the wild things roam

South Africa’s most Endangered carnivore can’t be kept in by fences. Wildcards chatted to the man re...

Rio Button

February 23, 2021 · 10 min read

Rumours of an elusive feline in the mangrove forest

While collecting data in San Pedro de Vice Mangroves, in the Sechura desert, final year biology stud...

Rio Button

December 23, 2020 · 8 min read

South Africa’s last remaining white shark stronghold under threat

The Oceans Research Institute battles the impact of demersal longline fishing to safeguard great whi...

Rio Button

November 25, 2020 · 8 min read

Malaysia has marine mammals?

90% of Malaysians don’t know there are dolphins and whales in Malaysian waters There are at least 6 ...

Rio Button

November 17, 2020 · 9 min read